In the present environment, it's difficult to go a day without hearing about one cultural war or another. One offence given. One or more groups targeted. From the individual, to families, campuses, corporations and nations, we appear stuck in a downward spiral. But could it be that many of these issues are actually not isolated in the way they appear to be? Is there a single dis-ease beneath the siloed battles appearing on our human skin? This Easter weekend, I took my dog for a walk on a cold Toronto day. I was in one of the city's large parks, and there were many families out, just as I was, enjoying the day. A large dog suddenly came out of the bushes, and lunged for mine, who was quietly walking on a leash. Thirty seconds later, another commotion; again the large dog had attacked another who was peacefully walking along a path. The owner of the attacked dog challenged the owner of the aggressive dog, and a verbal fight broke out. I won't repeat the language here, but let's just say that the aggressive dog owner vociferously defended his "right" to continue walking his dog, off-leash in the public park. In our cultural times, it would be easy to blame the category called "men", but the word that sprang to my mind on that Easter day, was selfish. It's the same word I think of in connection to many of the more serious abuses of power, within families as well as outside them. An individual can be fundamentally self-involved, and hostile to the other, just as a group or nation can. As William James pointed out, the self is not limited to the physical body. It reaches to what we're associated with: "a man's Self is the sum total of all that he CAN call his, not only his body and his psychic powers, but his clothes and his house, his wife and children, his ancestors and friends, his reputation and works, his lands and horses, and yacht and bank-account." James, Principles of Psychology 1890 So, it follows that our dogs are (in James' formula) experienced as an extension or part of our selves. Likewise, you and I may have a certain religious order, political persuasion, nationality, skin colour or gender, and feel as if those were a part of us. Hegel pointed out that beyond the self lies the other, a kind of binary opposite. And it is our attitude to the other that determines so much of the carnage in the world. There's something terribly tempting about sitting inside one category, and casting aspertions on another. That temptation is self, and it's often based on concepts of identity that are, quite literally, skin-deep. If you have grown up in a narcissistic family, literal or metaphorical, you know what being objectified and othered feels like. As a legitimate self, you are denied. To receive positive attention, you have to pander. Your persona is verified, rather than your true self. You probably know what it is to be made a scapegoat. The result is that you do not feel accepted as an part of the powerful "family". Relationships to the Other: Narcissistic Mature Denial Acknowledgment Disgust Interest Projection Curiosity Scapegoating Inclusion Reduction/Grandiosity Equality Objectification Subjectification Closed Open Hate Love Sometimes, we're forced to deny the other. Living in a busy city for example, means that it would be overwhelming to the psyche to acknowledge every passer-by, and to be open and curious about them. We can easily be nudged towards narcissism. Self and self-group exclusivity can easily be implicitly or explicitly encouraged. Othering is always but a regressive step away. Similarly, we oftenalter the psychological size of the other. We may be judgmental, or use categories to artificially define the other and make them smaller. At the same time, we make our self inflate and feel justified. It's not incidental to note that modern humans habitually treat nature this way. We commonly reduce it to a series of numbers or scientific descriptions. We categorize and utilize it. We often treat animals like things, or nothings. In psychoanalysis, writers like Lacan and Winnicott have long discussed how the other becomes real. We emerge from our own one-ness as babies, so that the (m)other is no longer just a good or bad narcissisticsupply, or an illusiory aspect of self. Communication, disillusion and the consequences of actions such as biting all contribute to a growth away from one-ness, and towards empathy, true relating and respect. The other can become real, though this is not guaranteed in individual development, and we retain an ability to return to self-centredness, and for a lifetime may find belonging in narcissistically-oriented groups. In my micro-example, the owner of the aggressive dog was narcissistically, not relationally, present. He was, in extension and effect, biting like a pre-empathic baby. The root of so many familial and societal problems is the same: we deny the other's existence in favour of our own. We reduce. We classify. We project, objectify and favour grandiosity. We fail to empathize and respect. But while it is important to address the existing damage and individual manifestations and symptoms we see about us, we should not ignore the underlying cause, which is not one of skin colour, gender, group or nation, but one of our common and problematic psychology.

0 Comments

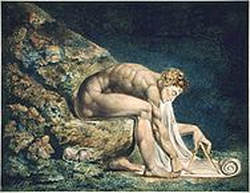

I recently read an enjoyable blog post by Mario Livio, a renouned astrophysicist. He'd taken umbrage with William Blake's depiction "Newton", as well as with Keats, who lyriced: “Philosophy will clip an Angel’s wings Conquer all mysteries by rule and line, Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine -- Unweave a rainbow...” Mr Livio goes on to say: "In my humble opinion, the views of both Blake and Keats were grossly misguided. Scientists are not blind to the beauty of the world. When I see an image such as the one taken by the Hubble Space Telescope that was dubbed “The Rose” (Figure 3), I believe that I am as capable to appreciate its exquisitely complex elegance as any artist." Sadly, this only demonstrates that Mr Livio doesn't understand Blake or Keats. Their assertion was not that individual scientists would suddenly be blinded to the beauty of the earth, as if a pair of mud-covered sunglasses would suddenly land on anyone practicing it. Like Jung, the real fear these artists had was that science would become its own mythos, and a cultureof materialism and reductionism would develop as a result. Jung refered to this as the mindset of "nothing but". Scientists are well-placed to resist the urge to reduce reality to current knowledge, since they are the ones who best understand their own subject. But it's hard to argue that the culture that science has gone a long way to create is not affected by a widespread misunderstanding of its findings. I've lost count of the number of clients who describe themselves as "nothing but" a collection of chemicals, and who are despondent at an empty, material universe. Their point of view is not scientific per se; in fact they have mistaken current knowledge for absolute knowledge, and are not conscious that science has always been, and always will be, progressive. In this respect, I'm reminded me of my own science teacher, who told my 1980's high school class that it was "virtually" 100% certain that there was no alien life anywhere in the universe, beyond Earth. What he was really repeating was an opinion, based upon his own knowledge, perspective and emotion on that particular day. Because science is progressive by definition, that opinion or hypothesis was liable to change as more knowledge was gained. In order to preserve the psyches of 25 budding atheists in the classroom, he would have been better served by talking about the limits of scientific knowledge, the age-old problem of hubris, and the propensity for humans to sacrifice mystery for guesswork. Had he done so, he might have been less stuck in a moment of knowledge, and more open to what he had no idea about. Therefore, in defence of Blake, I'd say he foresaw the dispiriting emergence of "scientism", a word yet to emerge in Blake's time, and eminently descriptive of the type of hubristic over-reach in the example above. Some things are mystery, some are knowledge. The latter has no claim on the former. Descartes assertion that science should make us "masters and possessors of nature" would have been anathema to Blake, and he might have agreed with Karl Popper when he said: “Science may be described as the art of systematic oversimplification.” This doesn't mean that scientists cannot experience beauty or awe, or that science's ever-increasing knowledge is not a wonderful and useful thing, but it does hint at an uneasy relationship with that which is beyond us. With a pinch of modesty, we might admit that some things always will be. If not, scientific discovery would have to cease at a certain point in time, and mankind would resemble an omniscient god, which is course, not something we moderns ought to believe in. |

Tom BarwellPsychotherapist, working in private practice online Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed