|

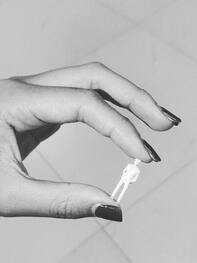

Trauma bonding can be a devastating and deeply confusing thing. We can find ourselves, knowing we’re in abusive relationships, feeling dependent on those very relationships, and riddled with guilt, shame and uncertainty about actions that have the potential to move us on in life. Sufferers often struggle to understand their feelings and confusion, and stay with what they know, even though they also know it’s awful and damaging to them. Trauma bonding is a complex psychological phenomenon that occurs in abusive or manipulative relationships, where the victim forms a strong emotional bond with their abuser. This bond is characterised by a mix of fear, loyalty, and affection, leading the victim to feel deeply attached to the person causing them harm. Understanding trauma bonding is crucial for recognizing and addressing abusive dynamics in relationships. This is especially true for narcissistic abuse environments. At its core, trauma bonding is a survival mechanism that helps individuals cope with abusive situations. When someone experiences repetitive abuse cycles, their brain can adapt to the trauma by forming a bond with the abuser. This bond is often reinforced by intermittent reinforcement, where the abuser alternates between periods of kindness and cruelty. This creates a sense of unpredictability, which can actually strengthen the bond as the victim becomes more focused on seeking the abuser's approval during the "good" times. To chase the “good” times, and the “good” relationship, trauma bonded individuals tend to prioritise pleasing and disappearing - physically, or through conformity. They try to become what the abuser wants them to be, whether this is “wallflower” absence, or a prop to their ego, or a tool to their stability… anything to keep the peace, and ultimately, to exact some measure of control over the situation, and thereby, their own internal regulation. Trauma bonding can be reinforced by a variety of psychological factors. For example, the victim may rationalize the abuser's behavior, believing that they deserve the mistreatment or that the abuser is acting out of love. This can create a sense of shared suffering or a belief that the abuser is the only one who truly understands them, further strengthening the bond. Breaking free from a trauma bond can be incredibly challenging. The bond is often deeply ingrained and can be reinforced by feelings of shame, guilt, or fear of retaliation. However, with support and guidance, it is possible to overcome a trauma bond and heal from the effects of abuse. One of the first steps in breaking a trauma bond is recognizing and acknowledging the abusive dynamics in the relationship. This can be difficult, as victims may have internalised beliefs that justify or minimise the abuse. However, therapy can be a valuable tool in helping victims recognize these patterns and develop healthier coping mechanisms. It is also important for victims to establish boundaries with their abuser and prioritise their own well-being. This may involve cutting off contact with the abuser, seeking support from friends and family, or accessing resources such as shelters or support groups for survivors of abuse. Developing a strong support network can help victims feel less isolated and provide them with the encouragement they need to break free from the trauma bond. Understanding the way such environments have impacted self-esteem is crucial. Survivors of such environments are often dependent on an abusive, manipulative individual(s) for any fragment of esteem, and their orientation for gaining esteem tends to be external: toward the dominating, abusive force in their lives. Realising this, and wrestling a sense of true, reliable self-esteem into one’s own hands necessitates a form of intentional practice. For clients, there’s frequently a form of mindful intentionality that we come to learn: recognizing cues, and reorienting our focus to break the cycle. It is a dangerous thing to have one’s esteem entirely in the hands of an unwell or manipulative individual. A renewed attention to self-respect, boundaries, assertion, interests and direction become crucial to the kind of work I do with survivors of such environments. Regular readers of this blog may recall the analogy of a solar system: narcissistic individuals find myriad ways to become the sun, and for others to become dependent, minimised, revolving planets. Recovery from trauma bonding is nothing short of the recognition of self: a practice through which healthy reorientation can give you your own centre of gravity, progress and loving attention - both within, and toward desirable aspects of the world. This is taking control, taking the wheel in one’s own journey, which breaks the trauma bond as it takes hold and gains permission, strength and resilience. Survivors really do have to break out of powerful orbits that constantly try to draw them in, and down. In conclusion, trauma bonding is a complex psychological phenomenon that can occur in abusive relationships. It is characterised by a strong emotional bond between the victim and abuser, which is reinforced by a variety of psychological factors. Breaking free from a trauma bond can be challenging, and takes time, but with support, guidance and practice, it is possible to overcome the effects of abuse and build healthier relationships.

0 Comments

On the face of it, positivism is tempting. Rarely discussed, it’s often confused for scientific fact, or even truth itself. Arguably, it has defined our Western culture, while hardly being mentioned. It is also a prime example of our human proclivity to turn humanity’s narcissistic frailty into a false view of the entire universe: a modern day version of imagining the earth to be at its centre, around which all turns. Here’s a definition of positivism:

“a philosophical system recognizing only that which can be scientifically verified or which is capable of logical or mathematical proof, and therefore rejecting metaphysics and theism.” Oxford Languages One might say, following temptation, that of course, ridding mankind of the fuddle of the unknown is intelligent, reasonable and necessary. After all, so this argument goes, haven’t we had enough of nonsense like belief in witchcraft, bearded interventionist father-gods, fairies and other ridiculous superstitions? Of course we’re better off only believing in verified facts, otherwise we might as well believe not only in all the silly things our ancestors did, but we might as well expand our nonsense-beliefs to include things like flying spaghetti monsters, hawaiian pizza interventionist baby-gods, and invisible vampire mice that drink our dreams! "We cannot, of course, disprove God, just as we can't disprove Thor, fairies, leprechauns and the Flying Spaghetti Monster." Richard Dawkins Above all, the voice of temptation goes, it is tempting to think that science is positivism, that they are one and the same. There are, without doubt, many positivist scientists who’d agree, perhaps like Mr Dawkins…but then again, some, arguably greater voices say things like this: “I am not a positivist. Positivism states that what cannot be observed does not exist. This conception is scientifically indefensible…” Einstein So, who is right? Is Einstein declaring we ought to believe in the unbelievable? And…why on earth does any of this matter at all?! To my mind, as a psychotherapist, it matters because this is a part of our society, or as Jung might have put it, our collective unconscious. I have, for example, in my 14 years of practice, mainly worked with agnostic or atheistic people. Very few were religious, and of those few, some were quite troubled by their own beliefs in a strict, judgemental God. This is important because religion and spirituality describe a certain attitude toward the other, and that attitude is key to mental health. If, for example, we believe that everything “other” is a dead-zone of sorts, a void, nothing but blah, we are unlikely to want to move towards it in an enthusiastic manner, whether that “other” describes other people, other activities, other things, aspects of ourselves we have “othered”, or the grand Other that is inherent when we talk about religious or spiritual matters. And if our dominant cultural narrative does indeed other parts of ourselves, and the world about us, we are likely to struggle to see beyond an inherited cultural lens that distorts both other (devalued) and self (idealised), as well as the relationship between them. People, for example, who struggle to adequately care for their bodies may, in fact, be dissociated from their physicality. They have othered a part of themselves. Similarly, many people view themselves as “nothing but” chemicals and frame their mental wellbeing through this lens, as though ingesting different, or more chemicals would “fix” them. Joanna Moncrieff has recently debunked this view of the so-called “chemical cause” of depression. Returning to the question of our relationship to Everything, I find a majority of people have culturally assumed a philosophy rather than a fact. This philosophy, positivism, assumes that Everything is a void, populated by barren rocks, or, at best, a rare sprinkling of meagre phytoplanktonic alien life. It is a nothing, because nothing proven lives or exists there. Positivism encourages a form of projection, the inverse one might say, of the father-projection of the bearded God in the sky. The positivist projection is the projection of man’s narcissism, just as the above alternative is: it says that what we know, our evidence to date, is the Truth. Obviously, the idea that, because science cannot currently detect and measure things like imagination, love, consciousness, feeling and meaning - the fundamental building blocks of humanity, just as much as our biological underpinnings are - means that these and further qualities must be denied by unquestioned positivity. One might say of course a positivist culture has no God, no vital other to love and relate to: such a God must, by definition, have the very qualities that our current technologies cannot detect, even in people standing two feet apart - how could they possibly detect them elsewhere in a vast universe? If what is undetected (Unknown) is denied, it is, by positivist definition, void. It follows that, if we are at all interested in the notion of God or The Everything (Alpha and Omega), the first, and perhaps the only facet, that we must transcend, is our own narcissism. Only then can we stop projecting the positivist void, a strawman made of spaghetti, or the familiar character of a bearded man that resembles Santa Claus. “The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing that stands in the way.” William Blake Beyond these projections lies humility in the face of the Unknown, or, as Blake might say, infinity: being small and virtually blind in the scheme of things, we must acknowledge our limits, and the vastness of what is beyond us. Beyond narcissism, we note that we do not have God-like omniscience. We know some things, and that is wonderful. Science itself is wonderful. But a true scientist like Einstein acknowledges that the body of scientific knowledge is, by definition, cumulative. A hundred years ago, we knew far less than we do now. In a hundred years’ time, we’ll know a lot more than we currently know, unless we blow ourselves up, or ban the pursuit of science. In a thousand years, if all goes well, perhaps we’ll be able to point a consciousness telescope, or an imagination-o-metre at the sky to see whether we can detect these qualities beyond ourselves. But at the moment, these technologies do not exist. “every science is a function of the psyche, and all knowledge is rooted in it” C.G. Jung Until then, it’s wise to remain humble, and admit our limitations. Positive knowledge is an aspect of our limitation as much as our progress, and it’s a mistake to project a limitation as though it were a fact. You only need to take an example like quantum mechanics to see how even our notions of what material actually is can radically change, given time (spoiler alert: it’s a lot more complex, mysterious and interesting than we once imagined it to be). It’s an even greater mistake to pretend we can measure, define, or make any meaning whatsoever without relying on the very mechanisms that positivism struggles to acknowledge; after all, there is no measurement at all without a measurer who possesses immeasurable consciousness, imagination and curiosity. “it is a paradox of modernity that when we seek to apply scientific techniques and discourses, the soul—the seat of subjectivity—vanishes.” C.G. Jung This point, that positivism-based atheism is a function of the imagination has been skewered by scientists and artists alike. Blake argued eloquently that: “If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite.” One often hears respected writers arguing against their own projections, as if knocking over a straw man were an act of crazy rebellion. In fact, they are at best, yesterday’s arguments; whether knocking down the projection of a bearded angry man in the clouds, a spaghetti monster, or an interventionist father-santa who’ll bring you what you want if you’re “good”. It is of course, far harder to argue against things that are unknown, or unimagined. But this is exactly what humility would have of us: that we imagine (for we cannot stop imagining) that we are ants, blinking in front of the vastest of the vast. Acceptance of not-knowing - or ignorance - is the fundamental state of humanity. This doesn’t mean we eschew knowledge, learning or creativity: it means the opposite, with the caveat that we are always watchful of our proclivity to hubris. You can discern exactly these qualities in many of the greats, for example: "Hitherto I have not been able to discover the cause of those properties of gravity from phenomena, and I frame no hypotheses; for whatever is not deduced from the phenomena is to be called a hypothesis, and hypotheses, whether metaphysical or physical, whether of occult qualities or mechanical, have no place in experimental philosophy." Isaac Newton The problem of projection is a constant in science, because we are tempted at every turn to assume (project) that a mathematical theory, or even a word we have coined, explains something entirely, whereas in reality even the best scientific discovery is usually limited, and limited within those boundaries to showing a certain pattern or order which is meaningful or useful. The observer, or measurer, is always human consciousness, and the hypothesis, choice of experiment, observation and interpretation, are all influenced by subjectivity. The human mind is bound, because of its wonderful properties, to extrapolate meaning, images and stories from scientific discovery. But positivism is only evidence of poor and uncontrolled imagination. As science evolves, so does the positivist perspective. In one moment, a positivist will believe in one thing, because that is the limit of her evidence, whereas the next, she’ll believe another. A realist will, by contrast, be cautious at all times, and never believe they hold the truth in their hand. A positivist will be tempted to think they “know” the robin, due to its classification, biology, theory of evolution and so on, but the realist, while agreeing with, and loving this knowledge, will always be aware that a robin is deeply mysterious. We do not know, at root (she might say), know what life is at all. We don’t know why there is something, and not nothing in our hand, or why there is a hand at all, or what an earth we are as a (somewhat) awake being who is observing and questioning…we sit, ultimately, as mysterious points of consciousness, within a mysterious universe. Our knowledge, as Blake put so beautifully, can never change that. It is beautiful in itself, but only ever partial. If it is all we see, all we see is a narcissistic projection. Our place, as humans, always risks the distorted perspective that projection brings. Humility is therefore the basis of both truth, and all religious reverence: “He who sees the Infinite in all things sees God. He who sees the Ratio only sees himself only.” William Blake It is not inconsequential to note that, alongside humility and the withdrawal of projection, a loving, reverential attitude toward the other is often the place where great science and religions meet. The intersection of positivism with medicine and mental health I want to further my previous discussion around the problems and implications of positivism, which as mentioned in my last article, can result in a toxic form of scientism This problem, I believe, cuts to the root of the reason why psychotherapy - and mental health in general - is such a battleground for competing ideologies and treatments. In one camp sit psychotherapists like myself, who work in particular with the experience of being a human through time, from infancy to the present day. Because we work with experience, our focus sits in various areas, such as mind, trauma, relationships, development, consciousness, memory and emotions: what it means to be an experiential human over time. This might not sound particularly radical, but when you work with individuals (rather than statistics), you find yourself working with aspects that are inherently difficult or impossible to measure objectively. Psychotherapy is at root, a relationship, defined by asymmetry: the client brings an intense subjectivity, and the therapist brings intense, informed, active listening, interspersed with informed, artful responses. At root, since psychotherapy is informed by the experience of whole beings, we cannot be positivists. The reductive necessity, in-built to the positivist ideology, is simply anathema to the holistic realism of psychotherapy. Most aspects of human conscious existence are not amenable to positivism: how can you accurately and wholly represent human imagination, for example, or love, or any other aspect in a strictly statistical way? A toothpick collection, or a million matches, cannot sum up an old growth forest. “The statistical method shows the facts in the light of the ideal average, but that does not give us a picture of their empirical reality.” Carl Jung Individuals, in their experience of being alive, do not fit into the neat boxes that positivism requires. For example, it is easy to weigh a person on a scale. This gives a clear statistic that can be worked with. But how do you weigh grief, memories, relationships and insecurities? Even if you can approximate them, you can only do so by reducing their complexity. Once you have done so, what does that statistic actually mean, in terms of a person’s reality, and future well-being? If I, for example, give your grief a number of 4, is that real? How does my reduction of your grief help you? How is a number of 4 real, when grief can manifest in complex ways over time, or hide itself even from the person grieving? What is a number 4, except an insult to a person’s humanity? Grief, after all, can be tied in knots with guilt, self-esteem, personal history, trauma, depression, existential dread…Oh dear, this is a terrible avenue, because before we know it we’re back to a whole person, and therefore back to psychotherapy! “Scientific education is based in the main on statistical truths and abstract knowledge and therefore imparts an unrealistic, rational picture of the world, in which the individual, as a merely marginal phenomenon, plays no role. The individual, however, as an irrational datum, is the true and authentic carrier of reality, the concrete man as opposed to the unreal ideal or normal man to whom the scientific statements refer.” C.G. Jung Psychiatry is another example that has become, over time, more positivistic. It leans heavily toward brain, rather than mind, to the extent, sometimes, of dismissing or devaluing the latter entirely. Mind is almost a dirty word to strict positivism in this community. What matters tends to be chemical in nature, so that the voice of medical insecurity asks: if a psychiatrist isn’t prescribing, are they actually, positively, doing anything? I’ve lost count of the number of people I’ve met, who’ve gone to their psychiatrist, and left a few minutes later with a prescription in their hand, while feeling unhelped, and rather dismissed as a person. This is the nature of the sauce, so to speak: positivism has to dismiss the person. It cannot quantify experience, since it has no way to measure it and verify it…despite the deep irony that we can only ever measure anything by using mind, rather than brain! Indeed, in tune with quantum theory, we can say that so much, in reality, comes down to the qualities of the observer, and pretending this isn’t the case skews our perspective enormously. In a different vein, the school of “cognitive behaviourism” generally markets itself as “evidence-based therapy”, which is just about as positivist an assertion as one could get. This revealing phrase mirrors Freud’s own desperation to compete with the positivism of the natural sciences. In Freud’s case, he was haunted by Darwin, and longed to find the psychological equivalent of his groundbreaking theory of natural selection. One of the original behaviourists, Watson, wrote: “psychology as a behaviorist views it is a purely objective experimental branch of natural science. Its theoretical goal is … prediction and control” (1913, p. 158). He thought the purpose of psychology was: “To predict, given the stimulus, what reaction will take place; or, given the reaction, state what the situation or stimulus is that has caused the reaction” (1930, p. 11). It is as if he wants to reduce complexity to no more than a chemical reaction, and settles for the Pavlovian equivalent: human beings as statistical amoebas. The irony of the phrase “evidence based therapy” is that the majority of an individual’s evidence must be left in the trash bin when a statistical average is elevated to this degree. The mean idea of a clockwork man’s predictability in terms of cause and effect, measured in a laboratory, regularly misses and dismisses our complexity as human beings. Literature, the arts in general, humanistic psychology, psychoanalysis, phenomenology and analytical psychology all seek, by contrast, a holistic sense of being human, the pitfalls that lead to decline, and the alignments that encourage health and well-being. To my mind, no influences ought to be rejected out of hand. Behaviourism can be a useful influence, as can psycho-pharmacology: but in all areas, people who work in mental health ought to be well-versed in the dangers of reductionism, particularly when it flies undetected under the brilliant banner of science itself. The door to reductionism is always idealism, the chasing of theory and abstraction, rather than understanding and working with real people. Psychodynamic psychotherapists are not immune from pitfalls either, but the peril is not positivism, but rather issues of idealism of a different kind. Such idealists tend to wander interminably in the rabbit holes of a client’s past, or stick rigidly to singular theoretical doctrine, or slip into a cause-and-effect blame game on parental shortcomings. Psychodynamic theory is often difficult, even contradictory: some therapists seem to skip over much of it and favour friendship over the difficult work of psychotherapy. Advances in neuroscience, the link between mental and physical health, and our understanding of child development are all informing psychotherapy, confirming the accuracy of certain pre-existing theories as others fade. My own view is that we need to focus on real people, and to keep examining our own in-group biases. I work as an integrationalist, much informed by the psychodynamic school, including object relations and the many branches of psychoanalysis, as well as a working model of humanism. Humans are not automata, nor are they mere chemicals. They are not diagnoses or statistics. They are not averages or discrepancies. Neither can they be successfully treated through paradigms that mirror (or create) narcissistic environments of self-aggrandisement, reductionism and rejection. We would do well to remember that. Beyond mental health The issues created by philosophers who don’t realize they’re philosophers go well beyond competing mental health paradigms. Medical practice in general is easily tipped off balance, to damaging effect, by this issue. For many years, for example, medicine has struggled with patients who complain of serious ill-health, but who lack what a positivist demands: undeniable scientific proof of a known disease, preferably, a biochemical test, such as a blood test. In our era, diseases such as fibromyalgia, ME/CFS, Long Lyme and Long Covid, are often deemed “invisible”, in large part because science can't yet zero in on them. These diseases which are currently devastating the lives of millions of people and their carers. Often sufferers are dismissed, or referred to mental health resources under suspicion for being delusional (psychotic), or under the suspicion that they are somatising their anxiety. In these circumstances, there is rarely any conscious admission on the part of MDs that they are actually taking a philosophical position that prejudices the limitations of knowledge in a moment of time, over reality. This is not only because there is no chemical test for these diseases at present, but also because subjective knowledge must be discarded from the positivist’s perspective. Subjective knowledge, meaning the information from the patient, about their own symptoms and suffering, is experiential knowledge, and experiential knowledge is not the objective, replicable, statistical knowledge that positivism demands. Experiential knowledge, and subjective reality as a whole, infers a mind that goes far beyond the observable brain: it is as anathema to positivism as God is. "God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we, murderers of all murderers, console ourselves? That which was the holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet possessed has bled to death under our knives." Nietzche (1882)  Pronounced: Silla and ca-rib-dis If you’re not familiar with this Greek myth, recorded by Homer, here’s a (very) brief recap. Our hero, Odysseus is on his perilous journey. He’s on a ship, near to the Southern Italian coast, and has to navigate something extraordinarily difficult. His path is blocked: on one side, up ahead, waits Scylla, who is a multi-headed sea monster. Scylla would like nothing more than to bite him into pieces and devour him. On the other side, and perhaps even more dangerous, lies Charybdis, which is a terrifying whirlpool, ready to suck him and his ship down into oblivion. The situation Odysseus encounters is impossible to navigate, because avoiding one “monster” means coming within range of the other: there’s no way through without exposure. Odysseus is advised to sail closer to Scylla in the hope it would devour only a few of his men, and not all of them. Charybdis on the other hand, threatened total loss. Survivors of narcissistic environments If you’re reading this, you’re probably a survivor. You’re probably a bit like Odysseus, trying to find your way through life’s difficulties and choppy seas. But unlike some other, more fortunate others who may see a clear passage ahead, you start to feel trapped, exhausted and stuck between these “monsters”. Scylla The vicious, hungry, devouring monster. Ask yourself this: do you find yourself becoming angry, or ruminating a lot about particular characters you encounter in life? I don’t mean anyone. I mean people who seem narcissistic. It could be a boss who doesn’t care, or an entire (probably telecoms!) company. Anyone really who lights that ancient fire in you - the place you were originally burned. For survivors, this danger signal is liable to fixate you. Without your awareness, you’re liable to start making this “other” the unpleasant sun to your Earth. You are, psychologically speaking, drawn near to this monster. You are consumed by her in a cycling repetition of relating to narcissism. I think of Scylla by a different name: the narcissistically-intoned traumatic other (NITO). Scylla or NITO, it doesn’t matter. What matters is your divergence into dysregulation, and away from safe passage. It’s not your fault: this has become a compulsion in you, a compulsive fixation on danger. A desire to control or expose it, or destroy it…only brings you into its waiting jaws. One body, many heads, narcissism comes in a selection of different manifestations. Maybe it’s someone who’s the perennial victim (who doesn’t really love or care about others). Ditto the arrogant “phallic” version. The image-merchant. The toxic hater. All narcissistic. All, even if only partial, liable to capture you, and throw you into projection and fixation…making the repetition of your past, traumatic reality return time and again in a repetition compulsion. Charybdis When we’ve had a hard day trying to deal with the NITO(s) in our lives, which we are unconsciously co-creating with objective reality through projection and compulsive fixation…we’re at risk of oversteer. Or perhaps we steered towards Charybdis in the first place: after all, why would we want to encounter a cold, rejecting, demanding and self-centred world/person/other in the first place? Charybdis has a different skill set to the biting, snarling, feeding energy of Scylla. It is a vast whirlpool of immeasurable strength. To survivors, this is the danger of slipping away, of disappearing and avoidance. Charybdis is the arch dissociator; the away-from defence mechanism that can take us over and take us down, without us even realizing what’s happening to us. Survivors are expert dissociators. By this I mean any psychological, or physical, ways of…well, the opposite of associating. Survivors want to avoid, to withdraw, to fuzz out, to numb, and avoid: to be away. If we’re not aware of our desire, and proclivity to dissociation, it will keep happening in a compulsive, repetitive way. To survivors, this is often experienced at a mammalian level: we want to go back to the nest, to comfort. And the nest is also the womb. And the womb is also the mother. It’s important to note that dissociation can take different forms, but this is the essence of it. By the way, we all dissociate! Being healthy means being able to to-and-fro with association and dissociation - meaning we all dream, we all get lost in thought, most of us watch TV and descend into its nest, many adults dissociate via substances like alcohol or marijuana. But that’s different from compulsions that keep us there, control our lives, and can turn into dependencies if we're not care-ful. The Twin Dangers Scylla and Charybdis really do create twin dangers. They are linked and keep us static, reactive and without clear direction. When we sail too close to either, we are tipped out of our ship: the ship being our regulated, authentic, intentional Self. We flip, in coping, between hyper and hypo arousal. We live a reactive life that exhausts every cell of our being. And what do we want, ultimately? Is it really to “fix”, reveal or destroy other people’s narcissism? Is it really to live a life of control? We usually can’t. And these patterns are liable to repetitively dysregulate and disorient you if you are stuck in them. Clear water between these dangerous “monsters” is a better, more realistic and rewarding aim. A calm passage. As the Greeks said: riding out a bit of damage from everyday human-narcissistic damage. A view that feels it’s an adventure, not a perilous fight to stay afloat. A guiding star - a destination we aim for that feels connected to us in an authentic, non-reactive sense. Ahh! Now, when that happens, we can fall in love with the journey again, and potential opens up before us. I don’t pretend it’s easy, but this is the work, the task we take on together. The nature of the Guiding Star is another story, and one I’ll return to soon in the Narcissist Survivors’ Club. Thanks for reading!  Assuming "an Empath" as your identity can: 1. Mask hypervigilance, which is a trauma response 2. Mask being a “suppliant personality” - a specialist in giving narcissistic supply 3. Mask a loss or lack of self/social authenticity 4. Mask a narcissistic, grandiose self-image. 5. Mask passivity: being a sponge to others' emotions, or a chameleon, a defensive way of hiding By contrast, integrated empathy is:

For survivors of narcissistic environments, self-empathy is crucial:

In Ontario the landscape has been significantly shaped over the past 300 years or so. Seen from the air, the rural areas are a tribute to rationality with their uniform rectangular fields. When you fly over Europe, fields appear by contrast to be a testament to organic growth. Like a patchwork quilt, these boundaries radiate out from the towns and villages unplanned, and form their own patterns of space claimed over time, interspersed with ancient woodlands and rivers. Whether here in Ontario or across the pond, those fields reflect something we need as people, something important about what we need in order to function as individuals and societies. For many people, the word boundary conjures the idea of division, as if that somewhat negative connotation is what we’re seeking when we assert them in our lives. But those hedgerows and fences are not solely to do with division; they are far more purposeful, more functional than that. Absolute boundaries are rare. This type of “no contact” boundary is asocial, the desired end of interaction, something we reserve for highly problematic individuals often at the severe end of the narcissistic spectrum. I think of this kind of boundary as oceanic in breadth, beyond even the function of castle walls - certainly beyond any hope of health or warmth passing over it. To follow the metaphor, the Atlantic was a “no-contact” boundary for millenia, prior to recent history. For the most part, our boundaries are not oceanic. They are not primarily to do with cutting people off. Their importance is much more to do with our essential need to assert our being in the world. From this perspective, boundaries have a primary purpose of self-respect, of grounding ourselves in space-time, of saying “I’m here and I’m taking up room”. Some people never really have to think about boundaries. Their function has been learned environmentally in their childhood homes and maintained ever since. But if you’ve grown up with narcissistic parenting, or you’ve been worn down by a narcissistic partner, the assertion of self in space-time is not a given. Not at all. A highly narcissistic person doesn’t respect boundaries because they do not perceive them accurately. The field is their field, and aspects of that field (you included) either promote this image or threaten it. You having boundaries, having a self-respecting existence, having a self that has integrity, difference, boldness and independence...in other words, you being a separate entity...is anathema to narcissistic control. A boundary therefore, whether by axe or acid, is something to be taken down. In maturity, we’ve grown out of the “one field theory” of narcissism. When we’re healthy, our empathy isn’t lacking, and it isn’t limited to self or other. We have empathy for both. Our boundaries are extensions of healthy egos, assertions of our existence and need for respect. Where our field meets another, the boundary is a meeting point. Rather than oceans or castle walls, we have fences with an aesthetic we like and a function of mutual respect. As in our backyards, we encourage flowers to grow, we have gates to pass through, we chat to one another and share both materially and emotionally. This is the social boundary. It’s our most common boundary, important, assertive, and functional, flexible and appropriate. Understanding and implementing social boundaries can be a real achievement in life, perhaps especially for those of you who have been drawn to this article. It is an achievement beyond the obvious because healthy boundaries are an assertion of your ego, your being, and your self-respect. It can take a lot of work even to find this self that needs respecting, and more work still to keep it that way. Pleading with a narcissist to do this for you is like asking the sun to only scorch the desert on Tuesdays. “There’s no such thing as a baby” wrote the psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott, a beautifully put statement on the psychology of babies, and how they exist not as independent psychological beings, but as a world-to-themselves. The external and internal worlds are not differentiated as ours are. The baby assumes magical control of the mother's breast, as if it were a part of its own world. This is the era of infantile narcissism, before the other exists as such, a kind of unity or dyad with their mother. Winnicott was making a comment for the ages. “I” is something so embedded in human language and experience that we rarely even think of it. We don’t need to explore the excesses of social media to notice its dominance. If a baby is too young to have an I and an other, but by the time it has become a child playing in the sand, they're very much there. The squabbles over who gets what and when. The puffed out chests: I did it! I got there first! My turn. “I”, when it first appears, is filled with narcissism. Then of course, the good-enough parents have to chime back: “Oh yes, well done. No, now you have to share - please give your sister some too.” Good-enough parents have spent a lot of time modelling and teaching self-other interactions: you and me, rather than you or me. The child grows, imperfectly, toward a balance of self and other. But the problem of I never leaves us. On the sunburned return home, the parent who’s driving swears involuntarily as she’s dangerously cut up by another, selfish driver: a rampaging I who, it appears, cares not a whit for her safety or that of her kids, still arguing in the back seat over who gets what and when. Back home, the news she reads is filled with devastation: wealth hoarding; wars; hatred and environmental destruction. I, I, I, our human gift, our legacy and our destruction. Despite all our progress in other domains, taming the I has proven difficult, to say the least. If the I is a tiger, it’s still very wild indeed. In psychotherapy, this issue falls under the umbrella of narcissism: the untrammelled dominance of I. The damage done to people who’ve had to survive such an environment is clear. But the great I is not solely found on an individual level. It’s also found on the group level in what is known as group narcissism. That car that cut you up? You notice it’s a group of youngsters, and they are all laughing at you as one, gesturing rudely as you struggle to calm down. Group narcissism tends to stick out like a sore thumb; it betrays itself because if you understand narcissism, you know what to look for:

Highly narcissistic groups do not display healthy narcissism. They are not devoted to their own collective self while also listening and respecting other groups - quite the opposite. Many groups are psychologically identical in this respect, whether on the playground or the battleground. There’s always a scapegoat, always devaluation of another group, and a dehumanization of those who do not fit the group’s paradigm. There’s always a grandiose idealization of the self-group. On the largest scale, the dynamics of group narcissism play out on both extreme wings of politics, organized crime, cults, nationalism and totalitarian religions. Cultural narcissism is broader still, and encompasses both individuals and groups within its framework. Our relationship to nature has been broadly a narcissistic one, for example: we have taken without respect, we’ve devalued the other ruthlessly (without ruth, meaning care). Cultural narcissism is also prevalent on social media and exploitative tv shows, and it’s present in the pervasive materialism that so haunted Carl Jung and determines so much about how we view ourselves. We are acutely vulnerable to narcissism in its different forms. We need an individual I, as well as a group I to which we can belong, and both individuals and groups must swim in cultural waters. We yearn for a sense of self, but the balance between self and other is a delicate one, one we often pay little direct attention to. We make particular and unconscious use of the abstract world and of language to devalue and to idealize: something no other species on earth has to contend with. We don’t think for a second about how we’re living in misery because we have a “perfect” (imaginary) version of ourselves that haunts our every move and leaves us never good-enough. We’re deeply unconscious about how simple and tempting it is for us to paint a picture of the other that is devaluative: it just happens. Slavery, abuse, neglect and devaluative ideology “just happens”. Echoist fawning over cultish, destructive leaders “just happens”: the self evaporates like mist in the morning. But what do we mean by how easy and unconscious it is for us to “paint a picture”? Along with consciousness comes our power of abstraction. In devaluation and idealization, abstraction (imagination) is key to our methodology. Think of a devaluation you have witnessed, received or committed (everyone does it), and you are probably remembering someone being thought of or spoken about, or portrayed, as something less than they really are. We can reduce people to objects, insects, or worms simply with the power of our minds. Words are the chariots of devaluation. Language is a supreme achievement in our species. It has helped build what I think of as the abstract world, something near to hand, an ever present which we confuse with reality all the time. Think for example of how you view the political party you oppose, a rival sports club, or your enemies. Are these generalised abstract and devaluative representations, or do they accurately reflect the reality of the individuals concerned? Devaluations are often caricatures. Idealization uses the same mechanism as devaluation. It doesn’t have to be the cultish leader that bewitches us into hero worship; it can be anyone - mother, father, lover, leader. When we idealize we don’t see the person in front of us; we see, without usually noticing it, a god or goddess, their live image projected like gossamer, the abstract world lying on top of the real person in front of us. Splitting refers to our tendency for binary (black and white) thinking. Splitting good from bad in glib, simplistic ways brings a particular form of violence to human relations. If we’re not frightened by how easily we lose any form of nuance in our relationships, perhaps we should be. Every human being is narcissistic. What determines so much of our character is the degree - where we lie on the spectrum of narcissism. In my work as a psychotherapist I hold to the concept of “healthy narcissism”. We all have an I that must be respected. We need to take up time, space, to have our own ideas and our own sense of reality in order to be healthy. At the same time, we need to recognize when we’re taking all the limelight, or using grandiosity like helium in a balloon, or using the projections of devaluation and idealization. The flip side of narcissism is “echoism” or “codependence”, where people are reduced to wallflowers, to pleasing the other obsessively. Echo is a character who uses a kind of narcissism-by-proxy. She knows how to disappear but keeps the central narcissistic requirement of specialness alive by being bound to it externally rather than internally. Such individuals often feel intensely anxious about taking up space-time as an individual. Existence feels dangerous to Echo, so she looks for - and often finds - her Narcissus. Between the extremes of narcissism and echoism lies the imperfect, dynamic world of interdependency, of give and take, existing and loving the existence of others. In mythology, Echo was feminine, and Narcissus masculine. But just as the beauty of myth and art allows us to recognize that these two are not necessarily separate beings at all - they are frequently twin aspects of one person’s psychology - their genders are interchangeable too. As humans, we live with narcissistic bubbles: individual, group, cultural. Our species has narcissism built into it, as Winnicott knew. Darwin, Copernicus and Freud all brought us up against our narcissism: we came from apes; our planet isn’t the centre of the universe; we’re not even ‘masters in our own home’ (mind). Democracy, environmentalism, the UN...so many of our efforts are, at root, an attempt to overcome our inherent dangerous narcissism. Religion too, often attempts to tackle it; how seemingly impossible it is for a consciousness to wrestle with its own eventual absence. For thousands of years, we’ve adhered to the notion that somehow not just consciousness, but something of our ego could survive death and exist forever in another place. Our own absence is not just frightening to us, it is unthinkable and we’re forever tempted to imagine our way around it. Okay, so therapists can be a wordy bunch! Here’s a snapshot of something a little more practical. I’ve sketched out some simple things to think about to challenge your own narcissistic impulses, which is often a better way around than getting angry with those we notice in others. These meditations are not exhaustive in the least - they are just meant as a sample, a beginning if you’re interested. It might be that technology will one day help us out of this pickle, but in the meantime, we have the ability to observe our own narcissism. So, take a quiet moment to self-reflect upon the following: Individual Narcissism Bullying, particularly in schools, but also online, in workplaces and in the home, has never been something we’ve been good at combating. There are a myriad of programs and efforts at “increasing empathy” and still more that seek to increase or induce guilt in perpetrators. What appears to be frequently ignored remains unconscious...that people bully because they enjoy bullying. Bullying is intensely narcissistic, on the individual and group level. If we never teach what sadism is, and that yes, as a species we’re fully capable of enjoying being utterly vile to other people, this problem won’t be dented, let alone solved. Ask yourself honestly: have you enjoyed devaluing others? If your answer is no, try again. This time, include yourself: perhaps, like Echo, you habitually devalue your own self in the world. Does this make you feel “good”? Feeling good about feeling bad is the root of sado-masochism. Give it a name. Look it in the eye. Interestingly, the word “narcissist” itself is frequently used as a devaluation. Group Narcissism At the moment, as it’s always been, there’s no greater societal danger than group narcissism, or tribalism. Today, we live in an era of mass projection, and our responsibility in this is a shared, human one. Here’s a meditative practice through which you can become more aware of your own part in these phenomena on an ongoing basis. First, be honest with yourself about some of the groups you despise. List a few; trust me, you have some. Next, back to the group narcissism checklist: grandiosity, idealization, devaluation and splitting. You’ll need to pay particular attention to the role abstract imagination is playing. Ask yourself: are you idealizing your own group? In other words, are you seeing it as a projection, rather than the thing in itself? What is the real picture, nuanced, warts and all, without its grandiosity? Remember, idealization is every bit as dangerous as the next issue: devaluation. Are you devaluing the other group - seeing it as a devalued abstract entity, just like a picture on the wall, rather than the complexity it truly is? What about its individual members: are they accurately reflected, or grouped together under a devaluative projection? Think of the language you use to talk of the other, think of the pictures you conjure with your mind. Finally - and by now some of this will have already been addressed: splitting. How much binary (black and white) thinking is going on in your views of your own group (your beyond-I) and of the other? Remember, language is a giveaway, even if you’re using it within your own mind. Cultural Narcissism Many clients I meet with have long since given up any formal sense of religion. But how can we cope without the comforts it once offered? One way of approaching this from the perspective of narcissism is to think about our concepts of individuality. We have a great deal of trouble wrestling with death because unconsciously we’re wedded to the idea we’re special, unique individuals. Consciousness itself creates this perception. Perhaps this is something of a mirage; when you die, another is still alive. Consciousness is not truly “lost” in death - it continues in the psyche of humankind, and probably elsewhere too. It’s not just your children, your work or an afterlife that “continues” you. In healthy narcissism, we recognize our need to take up time and space, our need for ego...but letting go of some of our narcissism can also be a great relief. An afterlife is right here, right now, in your fellow human beings, and even in other life forms. The historical, binary separation between our self-concept of humanity as conscious, and the natural world as unconscious, and thing-like is breaking down. We are all utterly unique, but also the same as one another. Remember that your own consciousness is going to struggle to imagine its own absence. The binary implications of death are intolerable for us, but we don’t need to conclude an afterlife with an intact ego, including our personal relationships and memories; and neither do we need to strive for genius or children as our only way of leaving a self behind when we’re gone. We can’t all be a Shakespeare or an Elton John; we can’t, and shouldn’t, all strive to leave behind a band of mini-me’s. Neither do we need to. It’s a wonder to be a spark of consciousness, but the flame goes on once the spark disappears into the night. On this planet and beyond, who knows how many flames, what colours, what fireworks...what inferno? Isn’t that beautiful enough? Depression can snag us, and take us down. It seduces us to shrink from the world and hide away. While summer’s balm welcomes us, winter pushes us back into our homes, toward comfort, known quantities and isolation. Here are five ideas that can help you challenge the call of SAD (Seasonal Affective Disorder) depression.

Be mindful that we’re in unusual times. The call to hibernate and withdraw into depression is likely to be stronger this year. We tend to avoid anxiety-inducing situations, and we can stick too long in the comforts of withdrawal. This is not a balanced place to be. Weather advises, but if it determines your being this winter, be wary of becoming SAD - seasonal darkness can become your darkness, and seasonal cold can beckon your drift toward isolation and emotional deep freeze. Feeling vital and engaged is something you can have greater control over than you might realize. This winter, take up the challenge and go against nature’s grain, till you can flow with it again come spring, and relax into summer.  In fighting a war, you wouldn’t treat the opposing navy, air force, army and civil service as unrelated hostile phenomena...or rather, if you did, you might be missing a key component of the battleground. But that’s exactly how we approach the effects of a single widespread psychological mechanism that is rampant in our society - as if each instance were entirely unrelated to the whole. Some of the forces opposing dreams of a higher civility include: bullying, racism, xenophobia, sexism, toxic work environments, scapegoating, narcissistic abuse and homophobia. Traditionally, we have fought each of these forces alone - as if there were no organizing principle behind the scenes, orchestrating the carnage before us. But is it possible that an unseen and devious enemy might be lurking just out of our vision, or are these phenomena actually as unrelated as they appear? The answer is yes, there is a common enemy, and that enemy has a name: devaluation. We’re natural discriminators, and easily dismiss what is not important to us from a very early age. If we didn’t, we’d be overwhelmed and unable to function. Our brain discriminates all the time. As we age, we purposefully increase our ability to discriminate, thereby devaluing aspects of our environment: we hone our disgust, language, categorization, ability to order, simplify and quantify. As we enter adulthood, these unique human tools help us to gain more control of the environment around us than any other species on earth. Our discriminating brains do not simply perceive the world as it is. Rather, we perceive a reality that has been conditioned, filtered and filled by our imagination. Contrary to popular myth, imagination is not only dreamy or expansive; it’s not something confined to creative writing or art. It can run in the opposite direction too, and contextualize self and other alike as something lesser than they actually are. This produces an abstract reality, rather than an “objective” one. A good historical example of this occurred in Babylonia around 8000 years ago, when the first cities were forming. Rather than physically counting animals in trade, and remembering who owed what, marks were made in clay tablets. These marks stood in for the actual animal, and via the birth of accounting, arguably became more important to people than the real world creature that the marks represented: the marks were units in math, accounting and trade. Separated from the animals, these abstractions could be considered and manipulated in any number of ways, without ever setting eyes on the life they described. Human beings inhabit a unique middle ground, balancing the inner realm of imagination with the external other. From an early age, we use the former to idealize and devalue the other, using these polarized narcissistic projections in order to deal with an outside world that is far larger than us and operates on rules we cannot understand. In adult relationships, idealization is present in the blindness of first love, and in our idolization of celebrities and cultish leaders. But as if these victories of abstraction over reality were not precipitous enough, we also have idealization’s ugly twin to deal with. Devaluation is a powerful psychological mechanism, so powerful in fact that it can be addictive, and become a modus operandi for the way we approach the world, while we conveniently overlook the inherent sadism buried within it. It’s hard for us to admit it, but we delight in our inherited power to devalue, just as we delight in our other powers of imagination. The sadism that crooks up the bully’s smile exists in much of our humour; it’s more difficult to construct jokes that are expansive and generous toward the other than it is to offer a satisfying put-down. Similarly, swearing relieves us of complexity and satisfies us because we are exercising devaluation over the Other. Our ability to use imagination to reconstruct what is given into a competing abstract reality of our own making places us “above” the natural world, in a position where we’re vulnerable to hubris. Our ability to survey, categorize and quantify from on high leads to successful prospecting of nature; it’s much easier to erase a portion of the Amazon once it is reduced to a set of numbers on a spreadsheet, shorn of awe, empathy, without the thunderstrike of love for the other and its infinite riches. We might not be aware of the devaluation, or of the tingle of sadism this power commutes, but it is present nonetheless. The dominance of both prospector and bully alike is based entirely on the power of devaluation. Jung was particularly disturbed by the devaluation that is inherent in scientific materialism, a trend that to this day seeks to abstract the individual into chemical components. Jung knew that the allure of this reductive doctrine was irresistible, and could be turned inward in self attack. As in his time, “nothing but…” and its variants remain classic indicators of devaluation. I’ve lost count of the number of clients who have referred to their particular suffering as “nothing but a chemical imbalance in my head”, and likewise to themselves as “nothing but a loser”, “nothing but a whiner” or other reductive equivalent, even as they nestle into depression. Many of our great modern societal movements are attempts to shrug off devaluation and the treatment that this psychological mechanism precipitates. A racist, for example, has a worldview tainted by abstraction. In a classic, narcissistic manoeuvre, they idealize their own skin and devalue others’. The other is frequently reduced to a “nothing but” while the perpetrator elevates their own being into a position of manufactured superiority. Likewise, many survivors of familial narcissism have grown up surrounded by what I sometimes refer to as a fairground mirror - the one that shows you a grotesque reflection of yourself, often much smaller than your actual self, or impossibly large and exaggerated - projected images which present the real child with the unending accusation that they are “not good enough” and cannot measure up. Such survivors have experienced what amounts to a formative relational trauma, leaving many terrified of the judgement (devaluation) of others, socially phobic, depressed, anxious or without direction. The uprisings of our time, whether individual or cultural, are not only battles over rights or historical maltreatment. They are also about self-esteem, self-image and about how we are imagined. They are about the psychology of scapegoating and group narcissism, and in particular the mechanism of devaluation. Societally, people are not only sick of being devalued, they want to shrug off its associated humiliation and shame; they have the newfound courage to speak encultured sickness out loud, even through their fear. They want to free themselves of the distorted lens that society has placed on them. They want to be recognized in the real, in the here and now, as legitimate human beings, worthy of respect. The same is true for many of the clients I meet. But the temptation is always there for individuals or groups, no matter who they are, to engage in negating spirals of devaluation toward one another - it’s a power we’re never taught we possess, let alone how to use it responsibly. Instead, to this day it orchestrates from the background, just out of sight, immortal, unrestrained, forever readying its troops.  Working online is different from meeting in person, but here are a few tricks to make it easier - particularly if you’re sharing space with others: 1. Putting even quiet white noise, music or radio on by your door can help confuse noise and maintain confidentiality 2. Use headphones to “hide” one side of the conversation. If your partner is with you in a small space, they can perhaps listen to media using headphones too - to create some extra privacy. 3. Coordinate therapy sessions with others’ outdoor exercise so you have the place to yourself. 4. If children have allocated screen time, coordinate this with your therapy sessions. Better still if they too have headphones! 5. Be conscious of the “digital divide”. If you’re aware that there’s an added layer that can restrict you from diving deeper into the work of therapy, there’s a better chance of overcoming it. 6. Don’t be afraid to ask for your time. You need your own time for your own health. Therapy time is a unique, directed and important part of your time - sometimes we need to verbalize this so we can make it happen. Therapy relies in part on us having a safe, confidential place to talk. It can allow us to let our guards down, and to drop into conversations we didn’t know we could have. By mimicking as much as possible the confidential set-up of a therapist’s office, we can still allow for that to happen. If you have other ways that help you approach online therapy, it would be great to hear them. Best wishes to all, stay safe and stay well, Tom  This title is actually a subversive question because it directs you towards a line of thinking: that the only solution to increasing reliance on alcohol, food, video games or cannabis lies in a prohibitive attitude of not doing something. Not far behind are admonishing complaints like: “I set limits but never keep to them. I’m beginning to hate myself.” Or “I indulge with a compulsive, secret rebellion - even though I know there’s no one I’m rebelling against. I have no will power.” Or the classic: “I know what I should do…but I don’t. I’m pathetic.” These are conflictual statements, each of which contains evidence of a power dynamic alongside compromised self-esteem. Who is this secret authority against whom we rebel, and then feel “bad”? Subversive actions roam these phrases like spies. If we dispense with the wrangling over who gets to wear the crown for a moment, we can ask a different question: “Where on your list of friendships is your particular indulgence?" You have an undeniable relationship with it, even a close one, so how high up the ladder has it gone? Perhaps we could agree that top of the list is a position best avoided. Comfort. Warmth. Dependability. The dissolution of anxiety and furrowed brows. These are qualities we naturally derive from close relationships with others, but also by our indulgences. We can think of compulsive indulgence in terms of a human need for relationship - and instead of relying on cycles of shame and failing prohibition, try to work on a balance in our relational world that helps us feel healthy and regulated. Diversity of relationships can help to free us from the binary, conflictual mechanics of desire and prohibition. We can use actions to further our deep need for reliable relationships - not just to other people, but to our physical, mental and emotional selves. We can reach out to nature. We can refocus on careers, hobbies and passions. We can exercise. We can apply ourselves to projects and improvement. Examples like these can help regulate emotions and lead us toward self-esteem in ways that an over-reliance on immediate gratification cannot. We crave regulation of our emotional worlds in times of crisis: it’s natural to do so. It makes sense that you’re reaching out to a particular relationship to help you achieve that - one that’s probably convenient and feels dependable. But if that dependence is being asked to carry the lion’s share of unpleasant, crisis-level emotions such as anxiety, boredom or despair, it might be time to diversify your portfolio, and thereby to respect the other relationships in your life. You never know - they might crave you back. Please note: This article is about dependency rather than physical addiction. |

Tom BarwellPsychotherapist, working in private practice online Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed