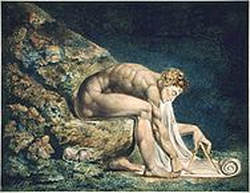

I recently read an enjoyable blog post by Mario Livio, a renouned astrophysicist. He'd taken umbrage with William Blake's depiction "Newton", as well as with Keats, who lyriced: “Philosophy will clip an Angel’s wings Conquer all mysteries by rule and line, Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine -- Unweave a rainbow...” Mr Livio goes on to say: "In my humble opinion, the views of both Blake and Keats were grossly misguided. Scientists are not blind to the beauty of the world. When I see an image such as the one taken by the Hubble Space Telescope that was dubbed “The Rose” (Figure 3), I believe that I am as capable to appreciate its exquisitely complex elegance as any artist." Sadly, this only demonstrates that Mr Livio doesn't understand Blake or Keats. Their assertion was not that individual scientists would suddenly be blinded to the beauty of the earth, as if a pair of mud-covered sunglasses would suddenly land on anyone practicing it. Like Jung, the real fear these artists had was that science would become its own mythos, and a cultureof materialism and reductionism would develop as a result. Jung refered to this as the mindset of "nothing but". Scientists are well-placed to resist the urge to reduce reality to current knowledge, since they are the ones who best understand their own subject. But it's hard to argue that the culture that science has gone a long way to create is not affected by a widespread misunderstanding of its findings. I've lost count of the number of clients who describe themselves as "nothing but" a collection of chemicals, and who are despondent at an empty, material universe. Their point of view is not scientific per se; in fact they have mistaken current knowledge for absolute knowledge, and are not conscious that science has always been, and always will be, progressive. In this respect, I'm reminded me of my own science teacher, who told my 1980's high school class that it was "virtually" 100% certain that there was no alien life anywhere in the universe, beyond Earth. What he was really repeating was an opinion, based upon his own knowledge, perspective and emotion on that particular day. Because science is progressive by definition, that opinion or hypothesis was liable to change as more knowledge was gained. In order to preserve the psyches of 25 budding atheists in the classroom, he would have been better served by talking about the limits of scientific knowledge, the age-old problem of hubris, and the propensity for humans to sacrifice mystery for guesswork. Had he done so, he might have been less stuck in a moment of knowledge, and more open to what he had no idea about. Therefore, in defence of Blake, I'd say he foresaw the dispiriting emergence of "scientism", a word yet to emerge in Blake's time, and eminently descriptive of the type of hubristic over-reach in the example above. Some things are mystery, some are knowledge. The latter has no claim on the former. Descartes assertion that science should make us "masters and possessors of nature" would have been anathema to Blake, and he might have agreed with Karl Popper when he said: “Science may be described as the art of systematic oversimplification.” This doesn't mean that scientists cannot experience beauty or awe, or that science's ever-increasing knowledge is not a wonderful and useful thing, but it does hint at an uneasy relationship with that which is beyond us. With a pinch of modesty, we might admit that some things always will be. If not, scientific discovery would have to cease at a certain point in time, and mankind would resemble an omniscient god, which is course, not something we moderns ought to believe in.

0 Comments

|

Tom BarwellPsychotherapist, working in private practice online Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed