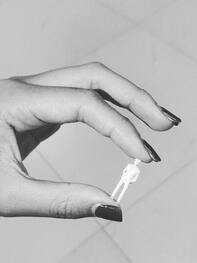

In fighting a war, you wouldn’t treat the opposing navy, air force, army and civil service as unrelated hostile phenomena...or rather, if you did, you might be missing a key component of the battleground. But that’s exactly how we approach the effects of a single widespread psychological mechanism that is rampant in our society - as if each instance were entirely unrelated to the whole. Some of the forces opposing dreams of a higher civility include: bullying, racism, xenophobia, sexism, toxic work environments, scapegoating, narcissistic abuse and homophobia. Traditionally, we have fought each of these forces alone - as if there were no organizing principle behind the scenes, orchestrating the carnage before us. But is it possible that an unseen and devious enemy might be lurking just out of our vision, or are these phenomena actually as unrelated as they appear? The answer is yes, there is a common enemy, and that enemy has a name: devaluation. We’re natural discriminators, and easily dismiss what is not important to us from a very early age. If we didn’t, we’d be overwhelmed and unable to function. Our brain discriminates all the time. As we age, we purposefully increase our ability to discriminate, thereby devaluing aspects of our environment: we hone our disgust, language, categorization, ability to order, simplify and quantify. As we enter adulthood, these unique human tools help us to gain more control of the environment around us than any other species on earth. Our discriminating brains do not simply perceive the world as it is. Rather, we perceive a reality that has been conditioned, filtered and filled by our imagination. Contrary to popular myth, imagination is not only dreamy or expansive; it’s not something confined to creative writing or art. It can run in the opposite direction too, and contextualize self and other alike as something lesser than they actually are. This produces an abstract reality, rather than an “objective” one. A good historical example of this occurred in Babylonia around 8000 years ago, when the first cities were forming. Rather than physically counting animals in trade, and remembering who owed what, marks were made in clay tablets. These marks stood in for the actual animal, and via the birth of accounting, arguably became more important to people than the real world creature that the marks represented: the marks were units in math, accounting and trade. Separated from the animals, these abstractions could be considered and manipulated in any number of ways, without ever setting eyes on the life they described. Human beings inhabit a unique middle ground, balancing the inner realm of imagination with the external other. From an early age, we use the former to idealize and devalue the other, using these polarized narcissistic projections in order to deal with an outside world that is far larger than us and operates on rules we cannot understand. In adult relationships, idealization is present in the blindness of first love, and in our idolization of celebrities and cultish leaders. But as if these victories of abstraction over reality were not precipitous enough, we also have idealization’s ugly twin to deal with. Devaluation is a powerful psychological mechanism, so powerful in fact that it can be addictive, and become a modus operandi for the way we approach the world, while we conveniently overlook the inherent sadism buried within it. It’s hard for us to admit it, but we delight in our inherited power to devalue, just as we delight in our other powers of imagination. The sadism that crooks up the bully’s smile exists in much of our humour; it’s more difficult to construct jokes that are expansive and generous toward the other than it is to offer a satisfying put-down. Similarly, swearing relieves us of complexity and satisfies us because we are exercising devaluation over the Other. Our ability to use imagination to reconstruct what is given into a competing abstract reality of our own making places us “above” the natural world, in a position where we’re vulnerable to hubris. Our ability to survey, categorize and quantify from on high leads to successful prospecting of nature; it’s much easier to erase a portion of the Amazon once it is reduced to a set of numbers on a spreadsheet, shorn of awe, empathy, without the thunderstrike of love for the other and its infinite riches. We might not be aware of the devaluation, or of the tingle of sadism this power commutes, but it is present nonetheless. The dominance of both prospector and bully alike is based entirely on the power of devaluation. Jung was particularly disturbed by the devaluation that is inherent in scientific materialism, a trend that to this day seeks to abstract the individual into chemical components. Jung knew that the allure of this reductive doctrine was irresistible, and could be turned inward in self attack. As in his time, “nothing but…” and its variants remain classic indicators of devaluation. I’ve lost count of the number of clients who have referred to their particular suffering as “nothing but a chemical imbalance in my head”, and likewise to themselves as “nothing but a loser”, “nothing but a whiner” or other reductive equivalent, even as they nestle into depression. Many of our great modern societal movements are attempts to shrug off devaluation and the treatment that this psychological mechanism precipitates. A racist, for example, has a worldview tainted by abstraction. In a classic, narcissistic manoeuvre, they idealize their own skin and devalue others’. The other is frequently reduced to a “nothing but” while the perpetrator elevates their own being into a position of manufactured superiority. Likewise, many survivors of familial narcissism have grown up surrounded by what I sometimes refer to as a fairground mirror - the one that shows you a grotesque reflection of yourself, often much smaller than your actual self, or impossibly large and exaggerated - projected images which present the real child with the unending accusation that they are “not good enough” and cannot measure up. Such survivors have experienced what amounts to a formative relational trauma, leaving many terrified of the judgement (devaluation) of others, socially phobic, depressed, anxious or without direction. The uprisings of our time, whether individual or cultural, are not only battles over rights or historical maltreatment. They are also about self-esteem, self-image and about how we are imagined. They are about the psychology of scapegoating and group narcissism, and in particular the mechanism of devaluation. Societally, people are not only sick of being devalued, they want to shrug off its associated humiliation and shame; they have the newfound courage to speak encultured sickness out loud, even through their fear. They want to free themselves of the distorted lens that society has placed on them. They want to be recognized in the real, in the here and now, as legitimate human beings, worthy of respect. The same is true for many of the clients I meet. But the temptation is always there for individuals or groups, no matter who they are, to engage in negating spirals of devaluation toward one another - it’s a power we’re never taught we possess, let alone how to use it responsibly. Instead, to this day it orchestrates from the background, just out of sight, immortal, unrestrained, forever readying its troops.

0 Comments

|

Tom BarwellPsychotherapist, working in private practice online Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed