1 Comment

Covid-19 has caught me unprepared, just as it has caught everyone unprepared. It’s taken me a few days to adjust, but now that I’ve made the move to online therapy and have had a chance to connect with many of the clients that rely upon our work together, I’ve had some time to think about some of the mental health challenges we’re all facing in these unprecedented times. My thoughts are by no means exhaustive, and I hope to add further information and articles as we progress through this event together. Based on my thoughts and conversations so far, here are a few common concerns it’s good to be aware of:

Taking action:

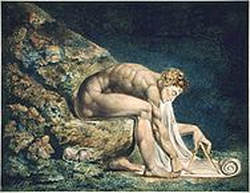

I send my best wishes to everyone out there. Stay safe. Take care of yourself and the others around you. Therapists like me are present, albeit online for now, if you’d like to connect. Tom [email protected]  I’d like to talk in this article about a specific kind of depression, linked with the stresses of growing up in the shadow of narcissistic parents. As I wrote in my last article “What is Narcissism”, a narcissistic parent is akin to Geocentrism: they have an insistent need for the Universe to revolve around them, and a concurrent, linked need to devalue the other. To quote the Highlander movie: “There can be only one!” Modern developmental psychology shows that one of the fundamental things that any young child has to do is to go into the world, to be mirrored and mirror, to give and receive, to see and be seen. This is a picture, though unequal in terms of size, age and power, of mutuality. If a parent is narcissistic, none of these vital things is going to happen on a reliable basis: narcissistic people do not relate mutually, but monadically - by which I mean they insist on their own perfection, perspective and “rightness” in an effort to maintain their superiority and stability and in so doing, deny the separate, legitimate existence of others. Narcissistic parents demand conformity unto themselves, a folding-in of their children and partners, and create an environment in which rebellion feels like the only alternative to submission - a false one as it turns out, since the narrative of rebellion remains in reality “all about them”. As an adult survivor of narcissism, it’s important to know how this has affected you. I’m going to use a fictionalized example to talk about how one outcome, depression, is experienced by many of the survivors I’ve worked with. Russian Doll In Russian, the name for a Russian Doll is Matryoshka . This is the type of doll, originally made of Linden wood, that comes apart in the middle to reveal another smaller, but otherwise identical version which also splits to reveal another, and so on until the smallest doll, which is always present at the centre. The word Matryoshka has its roots in the meaning: feminine, or mother. Likewise, it’s easy to see why people associate the beings inside, especially the smallest one, with babies. When I talk with adults with depression resulting from a traumatic relationship with a narcissistic parent, the conversation often goes in a similar direction. This is a fictional example, based on many real life ones. These are the words of “Alice”: “I want to get out of bed, feeling refreshed. I try to do it, but I’m groggy and tired. At work, same thing. I don’t even really feel a part of it...I’m removed somehow and can’t be bothered. Other people annoy me, I’m alone wherever I go, and it’s not just that I’m unhappy - I’m filled with uncomfortable feelings. I ache, I’m anxious, I’m full of dread and negative, morbid thoughts. It gets to the point where I hate myself.” In these words, you can hear a person who believes “I” to be a simple, unitary thing. To quote Freud (see previous essay), she believes that she’s “master of her own house”. Read more carefully, and you can hear tension between parts of her self, a bit like the parts of a Russian Doll. The outermost part can be heard with its adult, frustrated voice at the beginning of the paragraph; it appeals to the logical side of the speaker. She knows, after all, that getting up and feeling good is something she wants in order to experience health and vitality. But she’s confused and angry that the rest of her won’t play ball! This person, in the course of therapy, becomes aware of this strange tension, and comes to question the identity of her innermost aspect - the part she is so frustrated with. Over time, we come to see that this part is acutely sensitive to the outside world and that, when triggered grows intensely anxious, sometimes hateful and urgently wants to retreat from the world - a kind of inner flight. This is what has happened in our example above: the vital core of this depressed person has retreated, deep into the waters of the mind, and none of her frustrated everyday “outer” self does much to help. But why is this retreat happening in the first place? She asks. In response, I ask whether the innermost part of the Matryoshka might be able to tell us. This part of her sounds frightened, I say, as if it’s convinced the outside world will dominate, reject and humiliate her. Just like my father, she says, deep in thought: sometimes my mother too. Whenever I really needed to feel heard or seen, they got angry, as if I was criticising them, or they found another way to make it all about them. As we talked, Alice began to understand her internal world and to feel a greater measure of empathy for the traumatized, innermost part of herself. It’s not long before she recognizes the tone of her frustrated “logical” outer self - it carries the tone and even some of the language that her parents used to use on her, with the same net result: the devaluation of a wounded inner child and further retreat into depression. It’s not just external relationships that Alice needs to work on, but inner ones too. Just as the Matryoshka carries the baby, Alice needs to learn how to carry this vulnerable and highly sensitive part of herself. The innermost part of the Matryoshka never goes away, but she can learn to acknowledge it differently, listen to it carefully, and never again feel that it shouldn’t exist. A few months later, during which we continue our work together, Alice comes into my office with a broad smile. I ask her how she’s doing. She looks at me and holds my eye: “When I first came to see you I didn’t even know how stuck I truly was. I can’t tell you everything I’ve learned, but I want to say this to you: I know that depressed side of me now. I’ve learned how to love that vulnerable, scared, young part of me...and I will never ignore her again. I’ll never let her down.” Then she tells me of a memory that she’d held for many years, but had always concurrently dismissed: “I can’t remember how old I was. Maybe four. Maybe six, I don’t know. I was standing in the living room, alone. It’s very hard to explain, but I had an experience, like...I’d always imagined the world to be one way, and I was suddenly made to question it. In the old way, there was just my lens on the world. You’ll laugh, but it felt to my young self that the world was incredibly complex, but it made sense that way. The new way that I was wondering about was different, unimaginably complicated, so rich I couldn’t believe it didn’t fall to pieces or explode. The new way was filled with different lenses, as if each were a world in itself - how could that be?! How could reality all hang together like that without endless conflict ensuing? And yet, I knew it was true. I knew I had to accept it, and returned to it over and over for a while, wondering if I was just silly. At the same time, I eventually knew I’d reconciled myself to something very important, and that I might have become stuck if I hadn’t. Even so, thinking about it now I realize I was still stuck - life was an endless fight after that.” We had succeeded in bringing Alice out of her depression for now, but this innermost part of her would often want to tug her back and away from the world. Sometimes she’d talk about the baby Matryoshka sinking inside or wanting to panic and rage, and so dominate the entirety of Alice’s experience. We’d talk about how to honour, help and calm her. With our work had come a distinct memory in which she’d first wrestled with the idea of a multi-polar world - the realization of which her parents did everything they could to squash. From here on in, we’d return to this phrase of hers: I will never ignore her again. I’ll never let her down - a phrase which carried the sense that her vulnerability was no longer alone, hated and blamed out of existence. Taking herself seriously and learning self-care will require not only mindfulness, kindness, discipline, understanding but also so-called “healthy narcissism” - the ability for Alice to become her own being, her own centre that (unlike her parents) doesn’t need to devalue and deny the other, but instead is able to build on all the hard work we’ve done together and accept the existence of the other with nothing less than love.  A couple of years ago, I wrote a small article with this title, and it must have found a home somewhere on the internet, because I regularly receive enquiries about it. I decided it was high time I followed it up, so here goes. The concept of narcissism has moved mainstream, which can only be good news in my opinion. The more this issue is in our language and conversation the better, since the issue of narcissism haunts every human relationship - be it individual, group, political, economic or social. It’s something we just don’t seem to be able to grow through, perhaps because we’re often fixing the surface, rather tending to our underlying problematic trait. The second thing to understand about narcissism is that it’s ubiquitous: every human has a degree of it. But the degree of our narcissism varies considerably between individuals, and over time. The first thing to understand is: what on earth is it? Here’s my best current effort to describe narcissism: Freud (himself quite narcissistic) said that there were three great blows to mankind’s narcissism. The first blow came Copernicus, who the 16th century assured us that we were not that special - the Universe did not actually revolve around the Earth, but around the Sun, he said. The second came from Darwin, who assured us we were not made in God’s immutable image, but descended instead from apes. The third came from (of course!) Freud himself, who assured us that we weren’t even “masters of our own house” - we didn’t rule our minds; the unconscious did. I’d like to take the first example above as a way in to the question “what is narcissism?” Copernicus was actually reviving an Ancient Greek idea when he risked the wrath of the Catholic Church by promoting the idea of Heliocentrism (Sun as centre of the Universe) instead of the widely accepted “truth”: Geocentrism (Earth as centre of the Universe). But what does it say about mankind that until the modernisation of telescopes and empirical science in general, we actually believed the entire Universe revolved around us? There’s actually only one reason to suppose this quite laughable idea is true: narcissism. Or, put another way, the unquestioning belief that we are special, and that everything revolves around us. Now, the concept of Geocentrism also exposes something else about narcissism: it is antithetical to the idea of mutuality and recognition. In other words, the Other, the other stars, sun and planets are in no way equal to the Earth. They are lesser, and their primary role is just to keep the revolving system going, with the Special One at the centre. Heavily narcissistic people are renowned for just these qualities: their maintenance, at all costs, of their own special status. They are perfect, and as poor Copernicus learned to his cost, they will defend the way they perceive the world at all costs. They have, you will have noted, an inflated sense of their own importance, and engage in a concurrent devaluation of the Other. If you are that Other, your “job” is not to have your own, equal and recognized identity, but to affirm and fit into the narcissistic person’s worldview. This is why the psychological harm inflicted by narcissistic people can be quite severe. If you’re the child of a narcissistic person, you’ve been negated, devalued and pressured to fit into another person’s universe. A universe that revolves around them, in which empathy is an affront, and their entitlement is...well, an entitlement. You’ve learned to feel ashamed, at some level, of your own emergent being. This is a relational trauma, and one that can often lead to the constellation of symptoms often referred to as Complex PTSD (C-PTSD). If you’ve grown up under a Geocentrist parent, you had to buy into their perspective and conflate your identity with theirs, or you rebelled to become a scapegoat, and conflated your identity with rejection. Quite possibly, you oscillate between the two, and often you know the vortex of depression like the back of your hand, and cannot for the life you find a sense of direction that is your own. Good psychotherapy is, in my opinion, a unique way of meeting on a level playing field. Its work is to meet you where you’ve been lost, forgotten and unrealized: to help you develop out from the narcissistic person’s shadow, into your own self and out of theirs. Along the way, it’ll be important to talk about your anxiety, your depression and the times you disappear or camouflage. It’ll be important to speak and actually be heard. And remember: the Universe(s) is actually quite the reverse of our previous narcissistic understanding. It is far larger, far more interesting, more mysterious, and much more interconnected. Actually, the closest thing to a picture of a centre around which everything revolves in swirl of material supply is not the Earth at all, but a Black Hole.  The issue of identity is an important part of both life and psychotherapy. The following exercise is meant as a way to be curious about the way you conceive yourself and the selves around you, and to challenge what is preconceived.

You may have found that easy! If you didn’t, I think a great many people can empathize with you. Choosing a word or 3 to define your identity can be simple for some, but to others it feels reductive and unpleasant. Take a look at the list below. Do your words fit into one of these categories? Are there other ideas of identity that fit for you? Are there any categories that don’t? Do your identifiers form a kind of hierarchy, with some more important than others? Does this vary over space (environment) and time? The following ideas are not definitive; they are only meant to provoke thought and consideration. I’m sure there are others I haven’t mentioned, and many that I have mentioned may fit into more than one category. Paying attention to whether concepts of identity are group/individual or material/non-material can also be helpful and illuminating. Jung, for example, thought the Western world was fundamentally a materialistic one. Do you agree? Material — If your dominant identity is materialistic, you give a lot of importance to your physical being, to things and possessions. Examples include: skin tone, weight, beauty, height, money, possessions, a house, a reflection in the mirror. Psychological — Eg. Introvert, depressed, fun, rebellious, survivor, good, anxious, conscious, sad, optimistic, pessimistic, intelligent, creative, kind, conservative. Religious — A member of an organized religion. Is this a dominant consideration for you? Or perhaps you’re an atheist, or agnostic. Spiritual — Do you think of people (or yourself) foremost as souls, or as aspects of a divine being? Job — Does this define you or others? Do you introduce yourself by your job description, or identify others by their place on a work-based hierarchy? Class — Would you think to describe yourself as blue or white collar, working-class, upper, or middle-class? Is it important that you or others adhere to associated group values? Culture & Community — Some examples here might be military, creative or regional. Country — Is nation an important identifier for you? Personal/Ineffable — This might be a general, unworded or unwordable sense of self or character. Perhaps it’s associated with your name. Familial/Relationships — Perhaps identity for you is defined by relationships, whether they’re good, bad, multitudinous or otherwise. Age — Is “old”, “young”, “kid” or “middle-aged” a main identifier for you? Sex/Gender — To you, is this an important aspect of identity? Interests/Hobbies — Perhaps you define yourself by your tennis hobby, or being a recreational cyclist. Desires — We can define ourselves by what we want, or define others by their desires. Emotional — Perhaps how you feel defines you. Health/Ill-Health — You may define yourself or others by their health, or by their sickness. Beliefs — Veganism, for example, is an increasingly popular identifier. Politics — Eg. John is a right-winger/Erin is a Marxist. Memory & Narrative — To what extent are we defined by our memories, our stories and myths? The more I think about this subject, the more complex the question of identity becomes. The projection of identity, or even an insistence that a person adheres to our own (conscious or unconscious) idea of identity is more problematic still. A point to remember: when we’re reductive about another’s identity; when we try to categorize it narrowly or with shallowness, we can expect a defensive reaction. Reductive labelling disturbs many people, and is especially prevalent online. It’s a key characteristic of bullying and scapegoating as well as self-loathing. Clue! When used aggressively, the language of identity typically becomes reductive. Look out for linguistic clues such as: only, just, nothing but. Eg. I’m nothing but a… When conversations around identity are fraught, it’s usually because somewhere an attempt is being made to reduce the other to a category, or a narrow set of categories. This dehumanisation is often hurtful, and met with defensive anger.  Even if you don't agree with every detail of Carl Jung's writing, he's worth reading out of consideration for an alternative point of view on our present cultural situation. Jung lived and wrote through the Second World War, a time when hate and tribalism erupted into destruction. His conclusions don't really appear as a part of our dialogue in our present day conversation, if it can be called that - a remarkable fact considering his status as one of the two most influential psychologists of the last century. Jung was a prolific writer, with an encyclopedic knowledge of many topics, but strains of constant thought percolate through each book, like rich coffee. One such theme can be surmized as a critique of Western mind, which Jung thought was overwhelmingly extravert. Jung believed that Westerners, even religious unbelievers, held a perspective in which "man is small inside, he is next to nothing..."outside" (is) the only reality." By positing God, and Satan, as thoroughly external beings, Westerners had left themselves grovelling, empty, materialistic and powerless against the forces of their own unconscious minds. So alienated were they from their selves, they risked being dominated by Shadow - unconscious impulses, which could be highly destructive and lead to wars and destruction over property, wealth and surface-level differences. I have a suspicion that Jung would have nodded sagely, and sadly at today's world, for it seems that we have only exaggerated further what disquieted him the most. Our Western preoccupation with materialism has exploded, with resultant notable gains in the sciences in particular, but with it has come the dominance of image, elevated above all else. It has become ever more common for people to view themselves, and others through this inherited lens - one that denies the inner life almost entirely, and focusses instead upon surface identifiers like skin colour, gender, money, clothing and beauty. One of the risks of this attitude is to allow the unconscious Self, left in shadow, to dominate and run wild. When people talk about a present-day "culture of narcissism" they are often talking about this world that Jung described, and a resultant self-ishness, that has been encouraged until it dominates the social space in a field of rage. The grasping nature of a narcissistic, absented self, corresponds to the actions of an old-school bag vacuum cleaner, in which people are unempathically used as mere supply to fill a void. The narcissistic sufferer is in the painful position of continually warding off the terrors of emptiness, non-existence, and collapse through inflationand a never-ending cycle of needy value-seeking. In the present context, as in Jung's era, craving for individual attention and legitimacy has extended into Self-groups, defined by materialistic or superficial definitions of identity, which act as proxies for the narcissistic self. Lost in the clamour, outrage and "identity politics" on all sides, is exactly what was lost nearly a hundred years ago: a respect for our inner worlds as shared, rich and deepphenomena, intimately and ultimately connected with everything around us. "The soul is assuredly not small, but the radiant Godhead itself",says Jung in 1935, paraphrasing a section of the Tibetan Book of the Dead: "The West finds this statement either very dangerous, if not downright blasphemous, or else accepts it unthinkingly and then suffers from a theosophical inflation." Not for nothing, Jung's work has sometimes been referred to as an aspect of "depth psychology".  A little shout out to the man this morning who greeted the Tim Horton's server by name in the line in front of me, asked about her day, then went on his way with a shared smile. It was a telling micro-interaction, I felt, not least because it felt so different from the usual state of things. It was almost counter-cultural in fact. Personally, I've come to dislike the word "objectification" - it doesn't address the problem accurately, not least because we are all objects in the world. As an inverse, perhaps "subjectification" holds more validity. The man in the Tim Horton's line made the person behind the counter, quite intentionally, into an individual subject. No big deal, you might say, but of course, perhaps it isa big deal. Human beings are quite incredibly good at denying one another's subjectivity (often an "unknown"), and filling the resulting hole with projections. "Server" can very easily slip unconsciously to "that which brings me coffee" or the "coffee-thing". In the same way a man or woman can be reduced to a "threat-thing", or an "opportunity-thing" based on their biology, and unacknowledged complexity. In a world seemly dominated by identity politics on both sides of the political divide, mass society, and (perhaps not coincidentally) problematic online environments, respect for each individual we come across has become increasingly rare. It's as if we meet abstract ideas much of the time, rather than people; something which is dangerous, as well as superficial. Human beings have a terrible history of encountering one another as abstractions. Since an abstraction is not a true encounter, but an encounter of personally held and projected ideas, it is the breeding ground for all manner of monstrosity, allowing as it does for a reduction of one another to our own prejudice and desire. As a mechanism, projection and the denial of the individual other are both based upon expressions of self, rather than actual encounters. For this reason, the man in the Tim Horton's line was challenging the most destructive elements of narcissism in society, which are at risk of running amok. I hope this goes without saying: in therapy, we work with individuals!  What happens in a psychotherapist's office is a mystery to most people, and even those who attend sessions are usually unaware of other people's issues. So I thought I'd break the taboo, and let the reader in on a secret, the answer to the question: "what fear comes up the most often?" I'd say that claustrophobia, for example, is quite common. As is a linked fear of public transportation, particularly the subway and buses. Going beyond the boundaries of a known environment is another. But the largest group that I come across by far is the fear of other people, and within that category, the fear of being judged. On the surface of things, we can look at that statement, and be somewhat bemused. Why on earth would we so fear judgement? Does it really matter if other people look at us from under raised eyebrows, or act superior when we say something out of synch? Then again, judgement is what we also seem to fear the most in death. We propose an almighty being who's going to judge us after we pass, and dole out unimaginable punishment to those he (or she) finds lacking, according to strict criteria. The punishment specifically involves being cast out from a place of love, into tortuous hell. One of the problems with social anxiety is that we make our own fears come true, as if they were a prophecy. We fear being judged and cast out, become very self-conscious, and retreat in order to control our anxiety. We've taken ourselves out of the context, when we want to be in it. We've lost our relationship with what we most desire. The importance of being in relation is present from birth. We want to attach, we want to relate, we want to find love and other people. The danger and consequences of an infant not gaining those secure relationships forms the core of object relations and attachment theory. But the dangers of being judged are written deeper still, into thousands of years of history. In our lineages of human experience, there is perhaps no greater danger than being judged, because to be judged is usually to be viewed partially. It is akin to being objectified and reduced. It is therefore, a precondition to the worst of human violence, and a precondition to being scapegoated and othered. Slavery, genocide, tribalism and the dangers faced by infants and children all have the same danger in common: that they might be judged to be a thing, an idea, a single word. Once this happens, we're reduced and vulnerable. To be cast out of parental love as a child, or a tribe of any kind, is a dangerous thing. We know it down to our bones, particularly if we've been raised in an environment in which that danger has already burned us. As children, we know when we've been treated as "just" a nuisance, "nothing but" a pest, as stupid, an object, or lesser than a sibling. It hurts and damages our sense of identity. We become wary, anxious, and watchful. Psychotherapy is a relationship that's highly attuned to help you navigate your emotional world. To let you in on another secret: therapists like me are fortunate to be able to be there when people begin to find the inner resources to tackle their social anxiety. It's quite something to see courage emerge to secure its own gradual reward. People will always judge, but when we're able to be present by virtue of our choice, we have wrested our will to relate from the cold talons of our fear.  In the present environment, it's difficult to go a day without hearing about one cultural war or another. One offence given. One or more groups targeted. From the individual, to families, campuses, corporations and nations, we appear stuck in a downward spiral. But could it be that many of these issues are actually not isolated in the way they appear to be? Is there a single dis-ease beneath the siloed battles appearing on our human skin? This Easter weekend, I took my dog for a walk on a cold Toronto day. I was in one of the city's large parks, and there were many families out, just as I was, enjoying the day. A large dog suddenly came out of the bushes, and lunged for mine, who was quietly walking on a leash. Thirty seconds later, another commotion; again the large dog had attacked another who was peacefully walking along a path. The owner of the attacked dog challenged the owner of the aggressive dog, and a verbal fight broke out. I won't repeat the language here, but let's just say that the aggressive dog owner vociferously defended his "right" to continue walking his dog, off-leash in the public park. In our cultural times, it would be easy to blame the category called "men", but the word that sprang to my mind on that Easter day, was selfish. It's the same word I think of in connection to many of the more serious abuses of power, within families as well as outside them. An individual can be fundamentally self-involved, and hostile to the other, just as a group or nation can. As William James pointed out, the self is not limited to the physical body. It reaches to what we're associated with: "a man's Self is the sum total of all that he CAN call his, not only his body and his psychic powers, but his clothes and his house, his wife and children, his ancestors and friends, his reputation and works, his lands and horses, and yacht and bank-account." James, Principles of Psychology 1890 So, it follows that our dogs are (in James' formula) experienced as an extension or part of our selves. Likewise, you and I may have a certain religious order, political persuasion, nationality, skin colour or gender, and feel as if those were a part of us. Hegel pointed out that beyond the self lies the other, a kind of binary opposite. And it is our attitude to the other that determines so much of the carnage in the world. There's something terribly tempting about sitting inside one category, and casting aspertions on another. That temptation is self, and it's often based on concepts of identity that are, quite literally, skin-deep. If you have grown up in a narcissistic family, literal or metaphorical, you know what being objectified and othered feels like. As a legitimate self, you are denied. To receive positive attention, you have to pander. Your persona is verified, rather than your true self. You probably know what it is to be made a scapegoat. The result is that you do not feel accepted as an part of the powerful "family". Relationships to the Other: Narcissistic Mature Denial Acknowledgment Disgust Interest Projection Curiosity Scapegoating Inclusion Reduction/Grandiosity Equality Objectification Subjectification Closed Open Hate Love Sometimes, we're forced to deny the other. Living in a busy city for example, means that it would be overwhelming to the psyche to acknowledge every passer-by, and to be open and curious about them. We can easily be nudged towards narcissism. Self and self-group exclusivity can easily be implicitly or explicitly encouraged. Othering is always but a regressive step away. Similarly, we oftenalter the psychological size of the other. We may be judgmental, or use categories to artificially define the other and make them smaller. At the same time, we make our self inflate and feel justified. It's not incidental to note that modern humans habitually treat nature this way. We commonly reduce it to a series of numbers or scientific descriptions. We categorize and utilize it. We often treat animals like things, or nothings. In psychoanalysis, writers like Lacan and Winnicott have long discussed how the other becomes real. We emerge from our own one-ness as babies, so that the (m)other is no longer just a good or bad narcissisticsupply, or an illusiory aspect of self. Communication, disillusion and the consequences of actions such as biting all contribute to a growth away from one-ness, and towards empathy, true relating and respect. The other can become real, though this is not guaranteed in individual development, and we retain an ability to return to self-centredness, and for a lifetime may find belonging in narcissistically-oriented groups. In my micro-example, the owner of the aggressive dog was narcissistically, not relationally, present. He was, in extension and effect, biting like a pre-empathic baby. The root of so many familial and societal problems is the same: we deny the other's existence in favour of our own. We reduce. We classify. We project, objectify and favour grandiosity. We fail to empathize and respect. But while it is important to address the existing damage and individual manifestations and symptoms we see about us, we should not ignore the underlying cause, which is not one of skin colour, gender, group or nation, but one of our common and problematic psychology.  I recently read an enjoyable blog post by Mario Livio, a renouned astrophysicist. He'd taken umbrage with William Blake's depiction "Newton", as well as with Keats, who lyriced: “Philosophy will clip an Angel’s wings Conquer all mysteries by rule and line, Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine -- Unweave a rainbow...” Mr Livio goes on to say: "In my humble opinion, the views of both Blake and Keats were grossly misguided. Scientists are not blind to the beauty of the world. When I see an image such as the one taken by the Hubble Space Telescope that was dubbed “The Rose” (Figure 3), I believe that I am as capable to appreciate its exquisitely complex elegance as any artist." Sadly, this only demonstrates that Mr Livio doesn't understand Blake or Keats. Their assertion was not that individual scientists would suddenly be blinded to the beauty of the earth, as if a pair of mud-covered sunglasses would suddenly land on anyone practicing it. Like Jung, the real fear these artists had was that science would become its own mythos, and a cultureof materialism and reductionism would develop as a result. Jung refered to this as the mindset of "nothing but". Scientists are well-placed to resist the urge to reduce reality to current knowledge, since they are the ones who best understand their own subject. But it's hard to argue that the culture that science has gone a long way to create is not affected by a widespread misunderstanding of its findings. I've lost count of the number of clients who describe themselves as "nothing but" a collection of chemicals, and who are despondent at an empty, material universe. Their point of view is not scientific per se; in fact they have mistaken current knowledge for absolute knowledge, and are not conscious that science has always been, and always will be, progressive. In this respect, I'm reminded me of my own science teacher, who told my 1980's high school class that it was "virtually" 100% certain that there was no alien life anywhere in the universe, beyond Earth. What he was really repeating was an opinion, based upon his own knowledge, perspective and emotion on that particular day. Because science is progressive by definition, that opinion or hypothesis was liable to change as more knowledge was gained. In order to preserve the psyches of 25 budding atheists in the classroom, he would have been better served by talking about the limits of scientific knowledge, the age-old problem of hubris, and the propensity for humans to sacrifice mystery for guesswork. Had he done so, he might have been less stuck in a moment of knowledge, and more open to what he had no idea about. Therefore, in defence of Blake, I'd say he foresaw the dispiriting emergence of "scientism", a word yet to emerge in Blake's time, and eminently descriptive of the type of hubristic over-reach in the example above. Some things are mystery, some are knowledge. The latter has no claim on the former. Descartes assertion that science should make us "masters and possessors of nature" would have been anathema to Blake, and he might have agreed with Karl Popper when he said: “Science may be described as the art of systematic oversimplification.” This doesn't mean that scientists cannot experience beauty or awe, or that science's ever-increasing knowledge is not a wonderful and useful thing, but it does hint at an uneasy relationship with that which is beyond us. With a pinch of modesty, we might admit that some things always will be. If not, scientific discovery would have to cease at a certain point in time, and mankind would resemble an omniscient god, which is course, not something we moderns ought to believe in. |

Tom BarwellPsychotherapist, working in private practice online Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed